Lecture 1: What is Security?

Security Definition

CIA Model for Security Goals (obviously not the end all be all)

Confidentiality:

- Keeping sensitive information protected

- Examples: passwords, personal data

Integrity:

- Ensuring only authorized entities can access or modify data the correct data

- Examples:

- Bank accounts

- E-boks (compromised by Netcompany)

- Personal accounts (Steam security incidents)

Availability:

- Critical systems must be accessible when needed

- Examples: NemID, medical records

- Note: This is somewhat debatable in certain contexts

Security as an Afterthought

Security is rarely the primary consideration in system design:

- Houses: Standard locks are easily compromised; windows prioritize light/views over security

- Bunkers: Contrast where security is the primary design concern

Software Security

Largely follows the same principles as physical security, applying CIA to digital systems, but obviously limited to software.

Risk Analysis & Management

Risk management involves understanding tradeoffs:

- Example: Home design balances aesthetics (windows at eye level) vs. security (higher windows or none)

Most systems initially prioritize functionality over security:

- Development often focuses on demonstrating working prototypes

- Security considerations are frequently deferred, leading to vulnerabilities

Lecture 2

Reflections on C’s “security” model • How and where (in the process) should it have been found? before the function was introduced. • How can it be mitigated/solved? adding a depricated warning • Are they C specific? (these examples are low level specific and exist in the compiler) • Can they be found using manual reviews? Static analyis? • Reflections on the importance of context when defining security (think microarchitecture attacks and “helpful” compilers)

STRCPY:

strcpy() in C does not perform bounds checking 12. This means that it doesn’t verify if the destination buffer is large enough to hold the source string, which can lead to a buffer overflow if the source string is larger than the destination buffer 12.

strcpy_s is considered safer than strcpy primarily because it helps prevent buffer overflows. Here’s why:

- Buffer Overflow Protection:

strcpy_srequires you to explicitly specify the size of the destination buffer. This allows the function to avoid writing beyond the buffer’s boundaries, preventing potential overflows 1.strcpydoes not perform this check, making it vulnerable to writing past the allocated memory if the source string is larger than the destination buffer 23.

strcpy() violates the following security rules:

- CWE-120: Buffer Copy without Checking Size of Input (‘Classic Buffer Overflow’) - strcpy performs no bounds checking, allowing buffer overflows when the source string exceeds destination capacity

- CWE-676: Use of Potentially Dangerous Function - strcpy is considered inherently dangerous

- CERT C STR31-C: “Guarantee that storage for strings has sufficient space for character data and the null terminator”

sprintf

sprintf has potential for buffer overflows because of bad bound checking like in STRCPY above 12:

- Buffer Overflow: The main issue with

sprintfis that it doesn’t perform bounds checking. If the formatted string exceeds the buffer size, it can lead to a buffer overflow, potentially overwriting adjacent memory and causing crashes or security exploits 2.

sprintf() violates the following security rules:

- CWE-120: Buffer Copy without Checking Size of Input (‘Classic Buffer Overflow’) - Like strcpy, it performs no bounds checking

- CWE-676: Use of Potentially Dangerous Function - It’s inherently dangerous due to buffer overflow risks

- CERT C STR31-C: “Guarantee that storage for strings has sufficient space for character data and the null terminator”

- CERT C FIO30-C: “Exclude user input from format strings” (if user input is used in the format string)

spectre/meltdown are very hard to avoid.

Lecture 3

Access Control and Security Models

Access Control Matrix

An access control matrix is a formal security implementation for an access control model that represents the permissions of subjects (users, processes) to perform operations on objects (files, resources) in a system.

Example of Access Control Matrix:

| Subject/Object | File1.txt | File2.doc | Printer1 | Database |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alice | Read, Write | Read | Read, Write | |

| Bob | Read | Read, Write | No Access | |

| Charlie | No Access | Read | No Access | Read |

| Admin | Read, Write, Execute | Read, Write, Execute | Manage | Read, Write, Admin |

- Each cell contains the access rights that a subject has on an object

- Implementation can be row-wise (capability lists) or column-wise (access control lists)

Lattice-Based Access Control

A lattice is a mathematical structure used to model security levels and information flow in a system.

Example Lattice Diagram:

Top Secret

/ \

Secret TS-A

/ \ / \

Confidential S-A S-B TS-B

\ / \ /

Public C-A

subjects with Top Secret clearance can read everything below them in the hierarchy

- In this lattice:

- Top Secret (TS) is the highest classification

- Public is the lowest classification

- Some classifications are compartmentalized (e.g., S-A represents “Secret with A clearance”)

- Information can only flow from lower to higher levels or to incomparable levels

Finite State Machine Model

A finite state machine (FSM) model formally describes system behavior through states, transitions, and actions.

Example State Machine for File Access:

┌───────────┐ authenticate ┌───────────┐

│ Locked │ ─────────────────> │ Unlocked │

└───────────┘ └───────────┘

↑ │

│ │

│ timeout/logout │

└───────────────────────────────────┘

States:

- Locked: File access is prohibited

- Unlocked: File access is permitted based on ACL

Transitions:

- authenticate: User provides valid credentials

- timeout/logout: Session expires or user logs out

Bell-LaPadula (BLP) Model

The Bell-LaPadula model is a formal state machine security model focusing on maintaining confidentiality in systems.

Example BLP Scenario:

| Subject | Clearance | Object | Classification | Operation | Allowed? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| User1 | Secret | DocA | Top Secret | Read | No (violates Simple Security) |

| User1 | Secret | DocB | Confidential | Write | No (violates *-Property) |

| User1 | Secret | DocC | Secret | Read | Yes (same level) |

| User1 | Secret | DocC | Secret | Write | Yes (same level) |

| User1 | Secret | DocD | Unclassified | Read | Yes (higher clearance) |

- Simple Security Property: User1 cannot read DocA because Top Secret > Secret

- *-Property: User1 cannot write to DocB because Confidential < Secret

- Both properties allow operations at the same security level

Access Control in Code and Taint Analysis

Taint analysis tracks the flow of untrusted data through a program to identify potential security vulnerabilities.

Example of Taint Analysis in Code:

// Tainted input (untrusted)

String userInput = request.getParameter("username"); // TAINTED

// Unsafe operation (SQL Injection vulnerability)

String query1 = "SELECT * FROM users WHERE name = '" + userInput + "'"; // TAINTED

// Safe operation (using parameterized query)

PreparedStatement stmt = connection.prepareStatement("SELECT * FROM users WHERE name = ?");

stmt.setString(1, userInput); // SANITIZEDIn this example:

- The input from

request.getParameter()is considered tainted - Direct use of tainted data in SQL creates a vulnerability

- Using parameterized queries sanitizes the input

Lecture 4 Web security

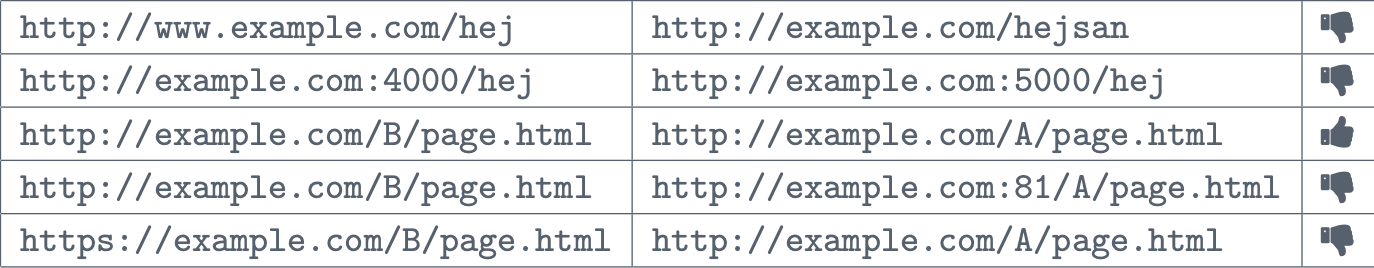

www.example.com and example.com are not the same because www is just a subdomain.

www.example.com and example.com are not the same because www is just a subdomain.

port 4000 and 5000 are not the same origin since different ports often run different applications or services that should be isolated from each other

the part after the domain and port is the same origin, thats literally how websites work.

port 81 and port 80 (http) are not the same.

port 443 (https) and http (80) are not the same.

Security is fun when you make sure you do stuff properly

- the user is the enemy

- sanitise your data

- properly protect your routes

- protect your api

- Use a proper cryptographic library

- dont push your auth tokens

Also client side scripting is a thing.

Lecture 5 web security 2

Access controll Sanitize your data. Self-tweeting tweet. tweet deck read text as if it should be executed.

- 1xx (Informational): The request was received and understood 45.

- 2xx (Successful): The request was successfully received 4.

- 3xx (Redirection): Further action is required to complete the request.

- 4xx (Client Error): The request contains bad syntax or cannot be fulfilled 6. A common example is the 404 error, meaning page not found 2.

- 5xx (Server Error): The server failed to fulfill an apparently valid request 6.

Lecture 6

A “reminder” / refresher on taint analysis

Lecture 3 at the bottom.

• An example taint analysis of a small program Lecture 3 at the bottom.

Uses

- Tracks untrusted data flow through applications to detect injection vulnerabilities

- Identifies SQL injection, XSS, and command injection risks

- Operates via static (code analysis) or dynamic (runtime) approaches

Limitations

- Misses implicit flows where tainted data affects control flow indirectly

- Struggles with custom sanitization recognition

- Context insensitivity issues - same data may be safe or dangerous depending on usage

- Performance overhead, especially in dynamic analysis

- High false positive/negative rates in complex applications

- Cannot detect sophisticated sanitization bypasses or logic-based vulnerabilities

Best practice: Use taint analysis as one component of a comprehensive security program rather than relying on it exclusively.

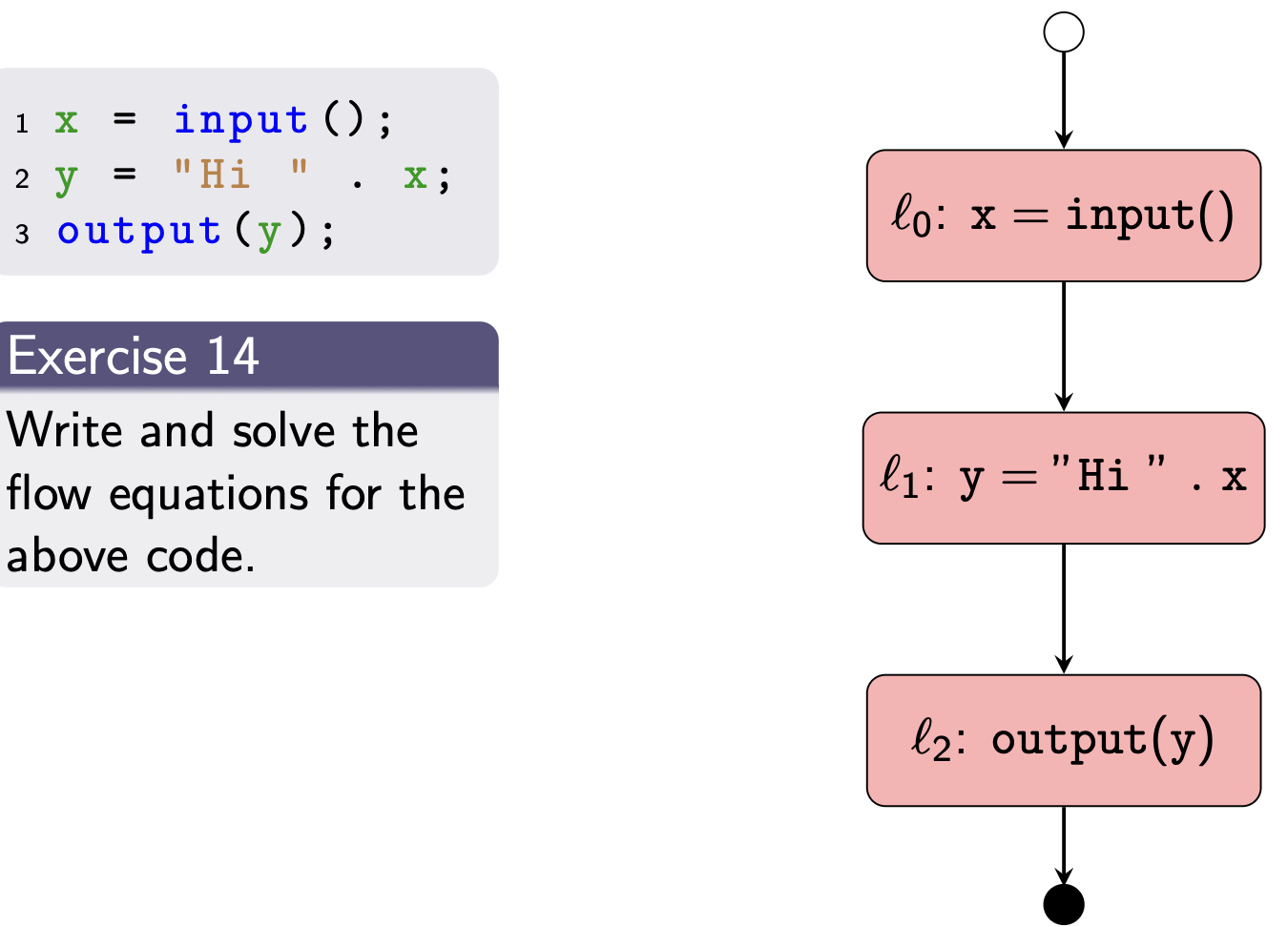

• Notes on lattices Lecture 3 • Notes on how to design a (taint-like) analysis

- Look at all your inputs and outputs and pick the worst case. • Notes on how to solve flow equations (even recursive ones)

- you just have to repeat the analysis until it doesnt change anymore, and then you take all your ins and outs (paths) and pick the worst case of them. • Notes on the work list algorithm

What it is: A generic graph traversal algorithm that systematically explores all states reachable from a starting point. It’s commonly used in computer science for tasks like model checking, program analysis, and graph exploration.

What it does:

- Starts with an initial state

s - Finds all states that can be reached by following transitions from the initial state

- Keeps track of visited states (

passed) to avoid revisiting them - Uses a worklist (

waiting) to manage which states still need to be explored

Key variations:

- Breadth-first search: Use a queue for

waiting(explores level by level) - Depth-first search: Use a stack for

waiting(explores deeply first) - Random: Choose states randomly from

waiting

Important notes:

- The algorithm always finds the same result regardless of search order

- Performance varies significantly depending on the search strategy chosen

- Terminates when the state space is finite and all reachable states have been found

Lecture 7 and 8 Formal methods

- Why do we need formal methods? • Explicit State Reachability Checking • Abstract Interpretation • The Uninitialised Variable Analysis • The sign analysis

Why do we need formal methods?

Formal methods are needed to find bugs in programs . The presentation emphasizes several key motivations:

- Game bugs demonstrate real-world problems - from speedrunner-exploitable bugs to frustrating gameplay issues

- Testing limitations - We can’t test all possible inputs, and traditional testing requires partitioning inputs into groups with similar behavior

- Security implications - An error may be an attack vector, making verification crucial in security contexts

- Verification throughout development - Formal methods can be applied at different stages from requirements to implementation

Explicit State Reachability Checking

Explicit state reachability checking explores the complete state space by executing programs with concrete values . Key characteristics include:

- Worklist algorithm - Uses a systematic search through all reachable states starting from an initial state

- State explosion problem - The number of possible states grows exponentially (8-bit: 255 states, 32-bit: 4+ billion states)

- Search strategies - Can use breadth-first (queue), depth-first (stack), or random approaches

- Completeness vs. scalability - While theoretically complete, it may not terminate for large programs due to infinite state spaces

Abstract Interpretation

Abstract interpretation executes programs with abstract values rather than concrete values to achieve termination while maintaining soundness . The approach involves:

- Abstract domains - Replace concrete values with abstract representations that capture relevant properties

- Sound approximation - Results are guaranteed to be correct (no false negatives) but may produce false positives because it can only check some code

- Termination guarantee - By using finite abstract domains, the analysis is guaranteed to terminate

- Trade-off principle - “You can only have two” of soundness, completeness, and termination

The Uninitialised Variable Analysis

The uninitialised variable analysis uses abstract interpretation with a simple two-element domain :

- Abstract domain Di = {⊥, ⊤} where ⊥ represents “uninitialised” and ⊤ represents “initialised”

- Transfer functions - Variable assignments set values to ⊤, while uninitialized variables remain ⊥

- Purpose - Detects potential uses of uninitialised variables before they cause runtime errors

- Memory handling - Memory operations return ⊤ (assuming memory could contain any value)

The Sign Analysis

The sign analysis tracks the sign of integer values using a lattice-based abstract domain :

- Abstract domain Dsign = {+, -, 0, ⊤, ⊥} with partial ordering where ⊥ is bottom and ⊤ is top

- Arithmetic operations - Abstract addition, multiplication, and comparison operations are defined with lookup tables

- Example operations:

+ + + = +,+ + - = ⊤,+ + 0 = ++ * + = +,+ * - = -,+ * 0 = 0

- Applications - Can detect division by zero, array bounds violations, and other sign-related errors

- Precision vs. efficiency - More abstract than explicit values but can be extended (e.g., distinguishing +0 and -0) for increased precision

CFA Program Extension for Whiley Language

Extend a Control Flow Analysis (CFA) program that processes Whiley language ASTs to handle all unimplemented visit methods and implement proper type checking.

1. Handle While Nodes

- Type check: Ensure the condition expression evaluates to boolean

- Evaluate: Process all statements within the while block

- Model branching: Create two control flow paths:

Assume(cond)- when condition is trueAssume(!cond)- when condition is false

2. Track Control Flow

- Preserve path information: Maintain start and end nodes for each visit method

- Enable traceability: Track where execution came from and where it’s going

- Support reachability analysis: Determine if error states (like assert violations) can be reached

3. Implementation Strategy

Each visit method must:

- Construct appropriate instructions

- Update CFA start/end nodes

- Maintain proper control flow connections

4. End Goal

Once complete, the CFA will enable static verification - analyzing program safety and correctness without execution by:

- Simulating possible program paths

- Checking reachability of error states

- Making statements about program behavior

Lecture 9 Fuzzing

What is Fuzzing?

Fuzzing is an automated testing technique that involves feeding invalid, unexpected, or random data as inputs to a program to discover bugs, crashes, and security vulnerabilities. The goal is to make the program behave unexpectedly or crash, which indicates potential security issues or bugs.

Blackbox Fuzzing

We only know that is crashes, put in random input and see what happens. If it doesnt crash then :thumbsup: if it crashes, then we know there is something we might want to handle.

Its hard because we dont know much, so knowing what to test and how to test is pretty problamatic which is where greybox fuzzing comes in since A Little Knowledge Goes a Long Way.

Greybox Fuzzing

it involves adding monitoring and measurement capabilities to software systems to gain insights and improve security. So if we know what part fails how it becomes a LOT easier to figure out what goes wrong and why. Fuzzing is great for detecting crashes and kinda garbage for Logic errors, which is why we try to get a little more information in greybox testing.

Whitebox Fuzzing

Whitebox fuzzing is pretty good for logic errors, but, REALLY tedious to make properly, and we all know the weakest link in the chain is the programmer.

Has a HUGE investment to do properly. • Requires difficult to use tools • Requires full access to source code • Requires working build system/platform (for target) • Instrumentation may change properties (e.g., timing

Generation vs Mutation-based Fuzzing

Generational Fuzzing

• Creates test inputs from scratch based on specifications or grammars • Knows the input format (like file headers, protocol structures) • More targeted but requires understanding of the input format • Example: Creating valid-looking PDF files with malicious payloads

Mutation-based Fuzzing

• Takes existing valid inputs and modifies them randomly • Easier to implement - just flip bits, change bytes, etc. • Less knowledge required about input format • Example: Taking a valid JPEG and randomly changing some bytes

Smart vs Dumb Fuzzing

Smart (Structured) Fuzzing

• Understands the input format/protocol structure • Uses grammars, specifications, or reverse-engineered formats • More likely to generate valid-ish inputs that get past basic parsing • Higher chance of finding deeper bugs but more complex to set up

Dumb (Unstructured) Fuzzing

• No understanding of input format • Just throws random garbage at the target • Super easy to implement and run • Good at finding basic parsing bugs but might not reach deeper code paths

Instrumentation

Instrumentation is the process of adding extra code or monitoring capabilities to a program to collect information about how it runs. In fuzzing context, instrumentation helps us see what the program is actually doing when we feed it our test inputs, rather than just “did it crash or not?”

Compiler-based Instrumentation

• Automatically adds coverage tracking code • Less manual work but requires recompilation • Examples: AddressSanitizer (ASan), coverage tracking in AFL

Manual Instrumentation

• Manually add monitoring code to source • More control over what gets monitored • Can track application-specific metrics • More work but can be more targeted

fuzzing improvements

Have some standard strings or whatever it should test. those things should be the most common things people get wrong. Essentially a common mistakes list it should go through. (yes i know it already exists but)