SIDE 1 (Front): Presentation Flow

Header

White-box testing (Ch. 3-4) | Test based on code structure, full implementation access

Key terms: control-flow graph (CFG), statement coverage, branch coverage, condition coverage, cyclomatic complexity

Three ==Columns: why whitebox instead of JUST blackbox==

Column 1: CORE CONCEPTS

Definition: Testing with access to implementation details

- Test based on program structure (control flow)

- Use Control-Flow Graph (CFG) representation (there is also data-flow testing instead)

- Nodes = basic blocks (statements)

- Edges = control flow transitions

CFG types:

- Program graph: each statement is a node

- Reduced CFG: consecutive statements merged

- Edge-labeled CFG: statements on edges

Key principle: Coverage ≠ quality, but helps identify untested code

Column 2: BASIC COVERAGE CRITERIA

1. Statement Coverage (line/node coverage)

- Execute every statement at least once

- Straight-line: 1 test case

- With branches: ≤ 2^b test cases

2. Branch Coverage (decision/edge coverage)

- Execute every branch (true/false) at least once

- Stronger than statement coverage

- Each if/while creates 2 branches

3. Condition Coverage (predicate coverage)

- Each atomic condition evaluates to T and F

- With short-circuit: stronger than branch

- Without short-circuit: incomparable to branch

Relations: Condition ⊇ Branch ⊃ Statement

Column 3: EXAMPLE - Simple Function

int foo(int x, int y) {

z = 0; // Line 2

if ((x > 0) && (y > 0)) { // Line 3

z = x; // Line 4

}

return z; // Line 6

}Statement coverage:

- foo(1, 1) → covers all statements

Branch coverage:

- foo(1, 1) → then branch

- foo(0, 1) → else branch

Condition coverage:

- foo(1, 1) → x>0: T, y>0: T

- foo(0, 1) → x>0: F, y>0: T

- foo(1, 0) → x>0: T, y>0: F

Note: Short-circuit evaluation means foo(0, 1) doesn’t evaluate y>0!

Bottom Strip:

When to use: Statement (baseline) | Branch (standard) | Condition (thorough) | MC/DC (critical systems)

Complexity: Computing coverage = run tests | Finding 100% coverage = undecidable

Connects to: Ch. 2 (black-box), Ch. 8-9 (integration)

SIDE 2 (Back): Deep Reference

Top-Left: ADVANCED COVERAGE CRITERIA

MC/DC (Modified Condition/Decision Coverage) Required for Level A avionics (DO-178B/C)

Five requirements:

- Statement coverage

- Entry/exit point coverage

- Decision to T and F (branch coverage)

- Each condition to T and F

- Each condition independently affects decision outcome

Independent effect: Change one condition, outcome changes (others constant)

Path Coverage:

- Cover every possible path

- Generally impossible with loops

- Motivates approximations

Basis-Path Coverage:

- Cover linearly independent paths

- Number of basis paths = cyclomatic number

- Stronger than branch coverage

Top-Right: CYCLOMATIC COMPLEXITY

Formula: V(G) = E - N + 2

- E = number of edges

- N = number of nodes

- Works for both full and reduced CFG

Interpretation:

- Number of basis paths

- Minimum edges to remove to break all cycles

- Complexity metric for code

Example:

A

/ \

B D

/ \ /

C E

\ /

F

|

G

V(G) = 10 - 7 + 2 = 5 basis paths

Possible basis: ABCG, ABCBCG, ABEFG, ADEFG, ADFG

Bottom-Left: COMPARISON TABLE

| Coverage Type | Strength | Test Cases | Decidability | Practical Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statement | Weakest | Minimal | Undecidable | Baseline |

| Branch | Moderate | ~2× stmt | Undecidable | Industry std |

| Condition | Strong* | 2^c tests | Undecidable | Thorough |

| MC/DC | Strong | c+1 tests | Undecidable | Critical sys |

| Path | Strongest | Infinite** | Undecidable | Impractical |

| Basis-path | Strong | V(G) tests | Undecidable | Practical |

*With short-circuit evaluation

**With loops

c = number of atomic conditions

Key formulas:

- Single if-else: 2 branches

- n independent if-else: 2^n paths

- Loop: infinite paths (bounded: depends on bound)

Bottom-Right: CRITICAL INSIGHTS

MC/DC Example Detail: For decision: a AND (b OR c)

Truth table with 8 combinations (R1-R8)

Independence pairs:

- a affects outcome: (R1,R5), (R2,R6), (R3,R7)

- b affects outcome: (R2,R4)

- c affects outcome: (R3,R4)

Minimal MC/DC suite: {R2, R3, R4, R6} (4 tests)

Common Fallacies: ❌ 100% coverage = complete testing

❌ Minimize test cases to achieve coverage

❌ Covered code is well understood

❌ High coverage = low fault rate (empirically false!)

What Coverage Actually Means: ✓ Shows which code was executed

✓ Helps find dead/redundant code

✓ Lower bound on testing quality

✓ Good for “no crash” requirements

✓ Encourages simple control flow

Goodhart’s Law: “When a metric becomes a target, it ceases to be a good metric”

Best Practices:

- Use coverage to find untested code

- Don’t optimize for coverage alone

- Combine with black-box methods

- Focus on meaningful test cases

- Coverage shows what was run, not what was tested

Data-flow analysis is also used in compilers and IDEs

•Some simple applications include identifying: • Variables that are defined but never used • Variables that are used before defined • Variables that are defined twice before used

Tips for Using This Sheet:

- During 4-min presentation: Focus on SIDE 1, use foo() example

- During discussion: Flip to SIDE 2 for MC/DC details and comparison

- Practice path: Define white-box → CFG → coverage types → foo() example → when to use

- If asked about MC/DC: Use example in top-left/top-right of SIDE 2

- If asked about complexity: Explain cyclomatic number (E-N+2)

- If asked about effectiveness: Mention empirical findings (coverage ≠ fault detection)

Connection to black-box:

- Black-box: specification-based (what)

- White-box: structure-based (how)

- Best approach: combine both!

- Black-box finds missing functionality

- White-box finds untested code paths

Second part ==WHy removing dead code is important = more secure, you cant exploit the dead code==

I’ll solve these exercises on software testing and verification for you.

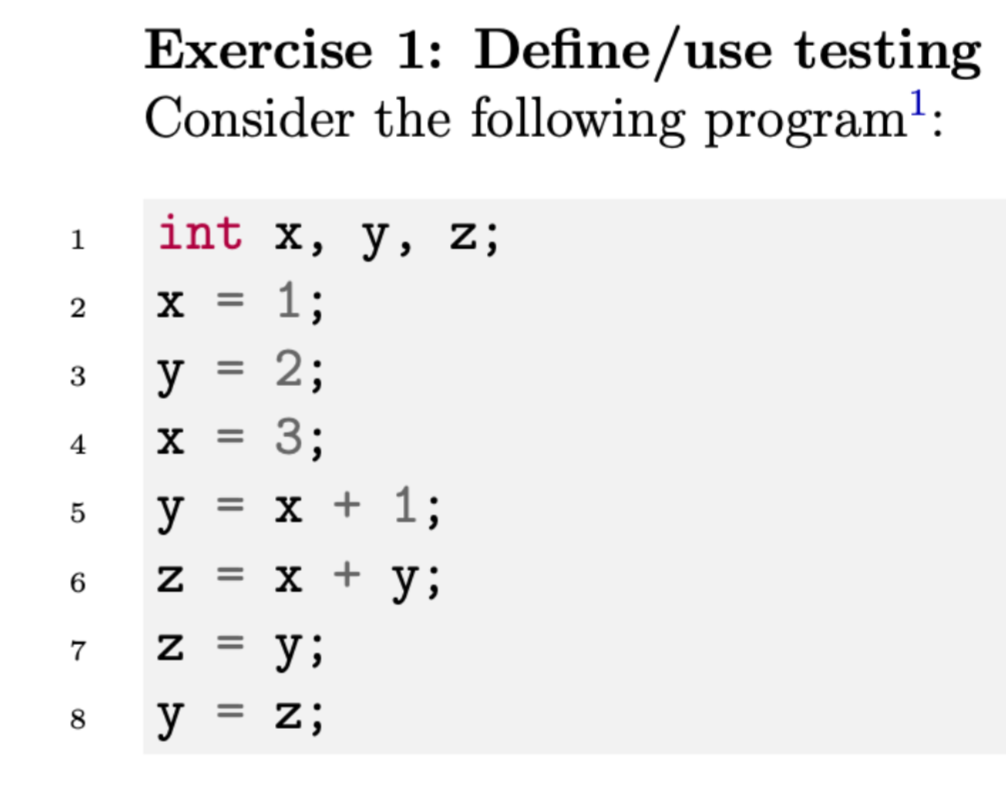

Exercise 1: Define/Use Testing

(a) List the statements/nodes n:

For the given program, analyzing each line:

-

DEF(x, n): n ∈ {2, 4}

- Line 2:

x = 1 - Line 4:

x = 3

- Line 2:

-

USE(x, n): n ∈ {5, 6}

- Line 5:

y = x + 1(reads x) - Line 6:

z = x + y(reads x)

- Line 5:

-

DEF(y, n): n ∈ {3, 5, 8}

- Line 3:

y = 2 - Line 5:

y = x + 1 - Line 8:

y = z

- Line 3:

-

USE(y, n): n ∈ {6, 7}

- Line 6:

z = x + y(reads y) - Line 7:

z = y(reads y)

- Line 6:

(b) All DU-paths for variables x and y:

For variable x:

- (4, 5): Path from DEF at line 4 to USE at line 5 (DC-path ✓)

- (4, 6): Path from DEF at line 4 to USE at line 6 via line 5 (DC-path ✓)

Note: DEF at line 2 creates no valid DU-paths because x is redefined at line 4 before any use.

For variable y:

- (5, 6): Path from DEF at line 5 to USE at line 6 (DC-path ✓)

- (5, 7): Path from DEF at line 5 to USE at line 7 via line 6 (DC-path ✓)

Note: DEF at line 3 creates no valid DU-paths because y is redefined at line 5 before any use. DEF at line 8 has no subsequent uses.

All DU-paths are DC-paths in this straight-line program since variables aren’t redefined along these paths.

(c) Implications about assignments in lines 2, 3, and 8:

- Line 2 (x = 1): Dead code - x is redefined at line 4 before being used

- Line 3 (y = 2): Dead code - y is redefined at line 5 before being used

- Line 8 (y = z): Dead code - y is defined but never subsequently used

These assignments are unnecessary and can be removed without affecting program behavior.

(d) Changes with branches and loops:

With branches (if statements):

- Multiple execution paths exist

- Variables may be defined in some branches but not others

- Need to track all possible paths from each definition to each use

- Some paths may be infeasible (logically impossible to execute)

- More complex path analysis required

With loops (while statements):

- Variables can be defined and used multiple times in iterations

- Potentially infinite number of paths

- Must consider 0, 1, or many loop iterations

- Same variable may have multiple reaching definitions

- Need dataflow analysis to handle loop-carried dependencies

Exercise 2: Simple Executable Slicing

(a) S(x, 6) - executable slice:

Working backwards from line 6: z = x + y

- Need value of x at line 6 → defined at line 4

- Need value of y at line 6 → defined at line 5

- Line 5 needs value of x → defined at line 4

- Need declarations

S(x, 6) = {1, 4, 5, 6}

int x, y, z;

x = 3;

y = x + 1;

z = x + y;(b) S(y, 7) - executable slice:

Working backwards from line 7: z = y

- Need value of y at line 7 → defined at line 5

- Line 5 needs value of x → defined at line 4

- Need declarations

S(y, 7) = {1, 4, 5, 7}

int x, y, z;

x = 3;

y = x + 1;

z = y;Exercise 3: Slicing

I cannot solve Exercise 3 without access to the referenced book material (Jorgensen’s “Software Testing: A Craftsman’s Approach”, Section 9.2.1, Figure 9.1, and Table 9.5). If you can provide:

- The commission program code or control-flow graph from Figure 9.1

- The slicing criteria from Table 9.5

Then I can compute slices S4, S7, S8, S18, S23, and S37 for you.